Andreas Grünschloß -- Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature - 2002

Aztec Religion and Nature (Precolumbian)

- Sacred topography: from mythic origins to a new Center of the World

- Cosmology, divination, and calendar

- A pantheon of life-sustaining forces and divine beings

- The preservation of nature through ritual and sacrifice

- Earth's vegetation, plants and flowers

- Underworld, death and Tenochtitlan's final destruction

In accordance with other meso-American traditions, the Aztecs experienced

"nature" in all its complexity not as a mere mundane entity out there, but

rather as deeply connected with superhuman powers and beings, manifesting

themselves in countless aspects of the surrounding world and a sacred

landscape. Earth itself, for example, could be viewed as a grand living being,

and in pictorial manuscripts it is often depicted as a monstrous caiman with

devouring mouth(s); hills are conceived as vessels containing subterranean

waters, with caves as sacred entrance. But from the beginning of creation and

the origination of life, man's activity and destiny is intertwined with an

unstable interplay of living cosmic forces, according to the Aztec cosmovision,

and human coping had to take place through a variety of ritual forms, since

nothing would grow, nothing would endure, if "our Mother, our Father, Lord of

Earth and Sun" would not be nourished continuously by ritual and sacrifice.

1) Sacred topography: from mythic origins to a new Center of the World.

Narrative accounts from the Precolumbian Aztec tradition trace the history

of the "Mexica" back into mythic beginnings. As in other mythic records,

especially of culturally and linguistically related peoples of the Uto-Aztecan

language-family, the creation(s) of man - or life, generally - took place in

subterranean bowels of earth: The Mexica are said to have finally "surfaced"

at, or through, "seven caves" (Chicomoztoc). Other sources speak about a

primordial dwelling on an island called "Aztlan" ("White Place", "Place

of Dawn/Origin"), and from this mythic location, probably somewhere in

Northwestern Mexico, they started a long migration (ca. 200 years) southward in

the eleventh/twelfth century. Roughly echoing the traceable history and

dissemination of the Nahuatl-speaking Aztecs from North to South, these

legendary wanderings led them via Coatepec (the mythic birth-place of the

important tribal and warfare numen Huitzilopochtli, "Hummingbird of the

Left" or "South") and the ancient Toltec City of Tollan finally to lake Texcoco

(Tetzcoco) on the central plateau of Mexico, where they first dwelled near

Chapultepec, and then in Tizapan. Upon Huitzilopochtli's divine advice,

the new and final residence Tenochtitlan (the center of today's Mexico City)

was established on a small island in lake Texcoco during the fourteenth

century. Within a very short time, this shaky Aztec settlement expanded into a

gigantic metropolis absorbing Tlatelolco on the neighboring island, with allied

city-states on the shores, and manifested itself as the center of an impressive

empire stretching already from coast to coast in the early sixteenth century.

Especially the culture-contact with the (remnants of the) Toltecs, generally

admired as "the" grand culture-giving predecessors, had a major impact on the

wandering Mexica, who would now look back on their former life-style as that of

rough "Chichimecans", of pure hunters and gatherers. Now, upon their arrival at

Tenochtitlan, they applied the construction of chinampas (the famous

"floating gardens") for an abundant cultivation of crops on the muddy shores

and lagoons, for example, and they adopted the Toltec sacred architecture in

building huge pyramid-shaped temples. The natural location of Tenochtitlan in

the middle of a salty lake also proved strategically safe for the originally

small bond of Mexica, especially since the island had fountains for supply with

fresh water. But with the fast growth in size, water supply became a problem

for the "Tenochca" (another name for the Mexica): Accordingly, an impressive

aquaeduct from the springs of Chapultepec was constructed. On the other hand,

dikes had to be built and foundation walls had to be raised, since Tenochtitlan

and Tlatelolco had been subject to severe floods every now and then during the

rainy season.

back to top

2) Cosmology, divination, and calendar. The communal life of the

Tenochca, as well as the construction of their society, was deeply intertwined

with religious and cosmological beliefs. Similar to other Amerindian and

meso-American traditions, the Mexica believed that other worlds ("suns") had

existed before this "fifth sun". Complex ritual strategies on all societal

levels had to safeguard life in all its forms from the lurking dangers of chaos

and destruction - dangers which, obviously, had already ruined the grand

city-states of the past (Teotihuacan, Tollan). Therefore, one finds a strong

notion of omnipresent peril, sometimes even pessimism, in Aztec poetry, and a

strong sense that the life cycle of this sun and of the rich center of power

and life in Tenochtitlan might also come to an end in the near future.

Therefore, divination, astrology and the general interpretation of "frightening

omens" (tetzauitl) were important means to be warned of possible

imminent perils. The famous "Book XII" of Sahagún's Historia

General gives an impressive account of such "bad omens" preceding the

arrival of the Spanish conquistadors (cf. opening paragraphs of Broken

Spears). Before the start of any important enterprise, one would consult

the "counters of days" (tonalpuhque), special priests with sound

knowledge of calendars and astrology. With reference to the vigesimal (based on

the number twenty) system of the tonalpohualli ("day count") calendar,

one had to be careful, for example, that the baptismal ritual of a newborn

child would not fall into one of the "bad" days: the "sprinkling of the head

with water" (nequatequilitztli) was postponed, accordingly, until a good

combination of one of the twenty day-signs and numbers (1-13) was at hand.

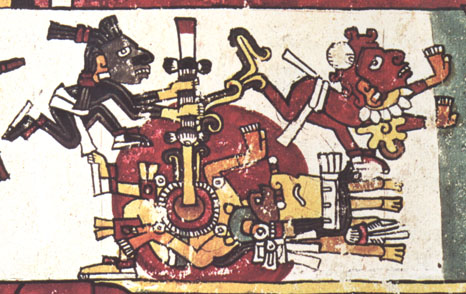

(1) New fire is

drilled on a victim's chest with a firedrill

(Codex Borgia)

|

Based on their astronomic tradition, the Aztecs knew the solar year of 365 days

(xihuitl), but the logical combination of twenty day-signs and thirteen

numbers led to an artificial tonalpohualli-cycle of 260 days (perhaps an

allusion to the human period of pregnancy?), which served basically as a

divinatory tool as explained in the "Book of the Days". The synthesis of both,

xihuitl and tonalpohualli, resulted in five "superfluous,

useless" (nemontemi) days per year - which were strongly associated with

misfortune (18 portions of 20 days = 360; plus 5). Shifting five days per year,

the start of every new year would move only between four (out of the twenty)

day-signs, resulting altogether in a logic period or "age" of fifty-two years

(13 numbers x 4 day-signs = 52), before another distinct 52-year "cycle" would

commence. And at the end of every such "age", it was always possible that this

world might now arrive at its termination and annihilation: this was the fear

during the final dark night after the last five nemontemi days of an

age, when all the fires had been extinguished, and when new life-giving fire

had to be "drilled" on the chest of a sacrificed human (cf. plate 1),

with the trembling hope that the sun might eventually have enough power to rise

again - for another age.

back to top

3) A pantheon of life-sustaining forces and divine beings. Life

is perceived as continuously endangered in the Aztec cosmos, but as a guidance

for coping with the hassles, challenges and dangers of life and nature, the

Mexica developed a differentiated, cumulative "way of life" or "religious

tradition" (verbal nouns of "to live" and "to be", like nemilitztli or

tlamanitiliztli, are used to denote the normative tradition of

"culture-religion-law"). And their huge pantheon of numina, divine powers or

gods (teotl) indeed covers all aspects of cosmic forces and powers of

nature with its polymorphic and often overlapping hierophanies. Some of the

numina have a special, prominent status - like Huitzilopochtli and the

important rain-god Tlaloc, worshipped together on Tenochtitlan's huge

double-pyramid "Templo Mayor". Others serve specific functions - like

Yacatecutli, "Lord in front", revered almost exclusively by the

wandering merchants. In some cases, the highest source of life seems to

transcend the polytheistic pantheon, and it can be addressed with singular or

dual names: One striking name is Ipalnemoa(ni), "(the one) through whom

one is living" (Live Giver), or Tloque Nauaque, "omnipresent one". In

dual form, one can speak of Ometecutli Omeciuatl ("Lord and Lady of

Duality"), denoting the ultimate ground of life and growth, as well as the

great celestial source of the human 'soul': "We, being subject servants,

from there our soul comes forth, when it alights, when the small ones are

dropping down, their souls appear from there, Ometecutli sends them down"

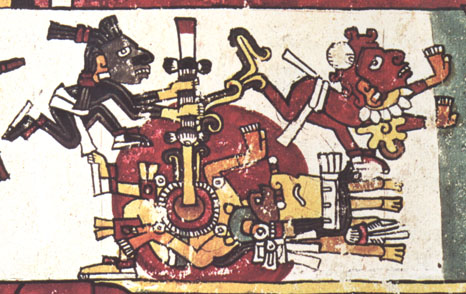

(cf. plate 2).Such a divine source can also be addressed as "old",

"true" or "sole God" (icel teotl), or as "Father and Mother" of all

gods/numina: "Mother of Gods, Father of Gods, old God, inside earth you

dwell, surrounded by jewels, in blue waters, between the clouds, and in the

sea". A binary aspect of the divine source of being and of natural

sustenance is "Lord and Lady of our flesh" (Tonacatecutli

Tonacaciuatl), bringing forth corn and all life-sustaining food.

(2) Ometecutli and

Omeciuatl place the human soul into a still lifeless skull

(Codex Fejerwary-Mayer)

|

Reflecting their prominent status in veneration, some of the more concrete

personal numina in the polytheistic pantheon could also be addressed with such

predications, be it the Trickster Tezcatlipoca ("smoky mirror") the

fire-god Xiuhtecutli or the famous Quetzalcoatl ("feather

serpent"). But it is also important to note that the "borders" of the Aztec

numina are often permeable, as well as the borders between divine and human

nature - i.e. between a god/numen (teotl) and its living human

representative, the so-called "image" (ixiptlatli) or "god-carer"

(teopixqui; generally translated as "priest"). In many instances, the

ixiptlatli is truly identified with the god/numen: he not only

wears the attributes, but he actually "is" Huitzilopochtli, Tlaloc or Xipe

Totec (etc.), he "is" the numen praesens - the actual earthly

impersonation of god. This so-called "nagualism" (from azt. nahualli,

"disguise") implies a simultaneous existence of the human nature with the

divine being, power, or person (as well as with certain mythologically

important animals, like the jaguar). This becomes apparent in the mythic

accounts of the Aztec wanderings under the leadership of the 'first'

Huitzilopochtli, where human and divine aspects obviously merge,

or in the narrations around the famous (originally Toltec) numen and

priest-king Quetzalcoatl of Tollan, who had a strong impact on Maya

traditions as well. But in the case of captives who were to serve as human

sacrifices, it is also reported that they did in fact represent the numen as

"true" and "living god" until their ritual death. This becomes most evident in

the case of the Toxcatl-ritual: A captive served as living

ixiptlatli for Tezcatlipoca for a full year; he was actually

venerated and adored as "Lord" and living Tezcatlipoca during this time,

but with the end of the year he was ritually killed and immediately replaced by

a "new image" of god.

back to top

4) The preservation of nature through ritual and sacrifice. Since the

cosmic order is "shaky", according to the Aztec cosmovision, man has to

preserve and safeguard this cosmos and its life-sustaining forces by continuous

ritual practice. An obvious, world-wide representation of the natural forces of

life is blood, and this view is very dominant and consequential in the Aztec

case. As in their paradigmatic myth, when the old gods had to sacrifice

themselves in the darkness of Teotihuacan, when they had to shed their own

blood in order to get the fifth sun moving, in the same way it is necessary for

the Mexica to keep "sun" Tonatiuh moving by a repetitive and ceaseless

supply with the so-called "precious liquid" (chalchiuatl) of human

blood. Likewise, several individual rituals of repentance or protection implied

ritual woundings for the drawing of blood (e.g. in the ears). To be sure, blood

sacrifice was not the only form of ritual; the Aztecs also used flowers, burnt

offerings, copal resin (incense), dance and music, but as the term

chalchiuatl already implies, human blood was supposed to be the

most "precious" and efficient life-sustaining offering. The extreme numbers of

ritual deaths, handed down via Spanish sources appear definitely exaggerated,

but there can be no doubt that human sacrifice was an important, significant

and - at least in the beginning of the 16th century - quite abundant ritual

method to keep the forces of nature alive. For example, a special ritual

warfare, the so-called "flower war" (xochiyaoiotl) had to be

institutionalized on contractual basis between the city-states of the Aztec

empire, simply to meet the increasing demand for supply with captives for

sacrifice.

As in other cultures, such human sacrifices seem to be dominant in case of

divine beings associated with the powers of fertility, sun, rain and

vegetation. - The tribal god Huitzilopochtli clearly carries solar

traits (apart from warfare), and his myth tells of a primordial sacrifice, when

he killed his lunar sister Coyolxauhqui and smashed her at the bottom of

"serpent hill" (Coatepec), a myth which had to be ritually performed and

re-actualized on Hutzilopochtli's festival (excavations at the bottom of Templo

Mayor uncovered a huge relief plate with her smashed body). - The distinct

sun-god, however, was "Sun" Tonatiuh, often depicted with red face and

body. Burnt offerings, flowers, and especially human sacrifices were used to

keep "Sun" on course. Tonatiuh was supposed to dwell in the "house of the sun

in the sky" (ichan tonatiuh ilhuicac), a paradisiacal place and a very

attractive postmortal region. In Aztec faith, the form of afterlife was solely

determined by the form of death, and not by any moral behavior. All warriors

who died on the battlefield and all the ritually sacrificed ones would be

allowed into this solar paradise - as well as all women who died during

confinement, since they were looked upon as warriors "acting in the form of a

woman". They accompany the sun daily, and after some time they would be

transformed into various beautiful birds or butterflies: like hummingbirds,

they would be sucking the flowers in the sky and on the earth. - Tlaloc

is the second most important god of the Aztec pantheon, representing

earth's fertility through water and rain. Accordingly, his nature - as well as

that of his wife Chalchihuitlicue - was ambiguous, like the nature of

water itself (fertilizing or flooding). As in the case of Tonatiuh, another

distinct postmortal region was associated with this deity in the rain-cloudy

hills (tlalocan): All people who died in floods or thunderstorms (e.g.

by lightning), or in connection with festering wounds (i.e. liquid), would

proceed into Tlaloc's paradise with permanent summer and abundant vegetation.

back to top

(3) Tlazolteotl

(with flayed skin) gives birth to Cinteotl

(Codex Borbonicus)

|

5) Earth's vegetation, plants and flowers. Within the

agricultural context of Aztec society, the different forms of vegetation - as

well as their divine representations - had a prominent status in ritual. The

god Xipe Totec ("Our Lord Flayer", "Our Flayed Lord"), generically

representing spring and vegetation, was mostly depicted wearing a flayed human

skin - a lucid symbolic representation of earth's new "skin of vegetation" in

spring, but also a clear hint to the ritual flaying of human victims related to

this godhead. Such bloody rituals took place on the festival

Tlacaxipeualitztli ("flaying of people"), where captives were skinned

and their hearts were cut out, presented up to the sun in order to "nourish"

the sun, whilst the living "images" or "impersonators" of Xipe Totec, called

Xipeme, would walk around, wearing the skin of the flayed ones. - Among

the female deities, those of earth, fertility, sexuality and destruction are

the most important. There are Mother of Earth or "Mother of Gods"

(Teteoinnan) deities, such as the old (Huaxtecan) earth deity

Tlazolteotl ("Eater of Filth"), associated with procreative powers and

lust, and important in rituals for repenting adultery, fornication etc.,

Xochiquetzal, representing love and desire, and associated with flowers

and festivals, or Coatlique (Huitzilopochtli's mother), with devouring,

destructive aspects. Tlazolteotl (cf. Plate 3) can also be

depicted with a flayed human skin (like Xipe Totec), and her

ixiptlatli was ritually flayed in the 'thanksgiving' festival of autumn,

where she - after meeting with the sun - gave birth to the corn god in a ritual

drama.

Several major plants were personified by special numina. The culturally

important maize (cintli), for example, had male and female divine

representations, like "Corn God" Cinteotl (or Centeotl) and,

among others, Chicome Coatl ("Seven Snake"), a prominent goddess and

generic embodiment of edibles. Goddess Mayauel represented agave and,

together with other specific pulque-numina, its fermented product, pulque

(octli). But as a matter of fact, the Aztecs were very rigid in allowing

access to alcohol, its abundant use being restricted to elder citizens.

- Apart from feathers (esp. of the beautiful Quetzal bird) or jade, flowers

(xochitl) were of special aesthetic and metaphoric significance in the

Aztec culture. Cultivated in rich abundance and serving as a common ritual

donation, flowers were not only synonymous with "joy", but also with "songs".

Hence, the flower theme appears in many lyrics (Cantares Mexicanos):

especially in the "flower song" (xochi-cuicatl) and "bereavement song"

(icno-cuicatl) dealing with death, impermanence and the recreation of

life through music and dance.

|

Flower Song (xochicuicatl)

Be pleasured for a moment

with our songs, O friends.

You sing adeptly, scattering,

dispersing drum plumes,

and the flowers are golden.

The songs we lift here on earth

are fresh. The flowers are fresh.

Let them come and lie in our hands.

Let there be pleasure with these, O friends.

Let our pain and sadness

be destroyed with these. ...

Only here on earth, O friends,

do we come to do our borrowing.

We go away and and leave

these good songs.

|

We go away and leave these flowers.

Your songs make me sad, O Life Giver,

for we’re to go away and leave them,

these, these good songs.

Flowers are sprouting, reviving,

budding, blossoming.

Song flowers flow from within you.

You scatter them over us,

you’re spreading them, you singer!

Be pleasured, friends!

Let there be dancing

in the house of flowers,

where I sing - I, the singer.

Cantares Mexicanos, folio 33v

|

From Another Flower Song

(of Nezahualcoyotl)

Let there be flower-singing,

singing with my brothers!

Intoxicating flowers have arrived,

narcotic adornments come in glory.

Let there be flowers. They have arrived.

Pleasure flowers are dispersed, they

flutter down, all kinds of flowers.

The drum resounds. Let there be dancing.

I am the singer, and my heart is painted

with a plumelike narcotic.

Downfluttering flowers are taken up.

Be pleasured.

Song flowers are bursting in my heart,

and I disperse these flowers.

Cantares Mexicanos, folio 28v/29

|

back to top

6) Underworld, death and Tenochtitlan's final destruction. According to

Aztec cosmology, all the 'normal' dead - even the great kings - had to go to

Mictlan, a subterranean place of unattractive afterlife with dark and

rather frightening features. The inevitable destiny of this "mysterious land",

or "land of no return", inspired many songs: "No one is to live on earth.

... Will you go with me to the Place Unknown? Ah, I am not to carry off these

flowers, singer that I am. Be pleasured. You're hearing my songs. Ah, singer

that I am, I weep that the songs are not taken to His Home, the good flowers

are not carried down to Mictlan, there, ah there, beyond the whirled ones".

In several of these songs, the vulnerable nature of life on earth and the

inescapable character of death appears combined with the sense of a deep

remoteness of God: "We will depart! I, Nezahualcoyotl, say: 'Be

cheerful!' Do we truly 'live' on earth? Not for all time on this earth, but

only for a little while. There is jade, too, but it crushes, even gold breaks,

ah, Quetzal-feathers crack. Not forever on this earth. ... What does Ipalnemoa

[Life Giver] say? Not any more, in this moment, is he, God, on his mat. He is

gone, and he left you behind as an orphan ...".

| |

A Song of Sorrow ( icnocuicatl)

We know it is true that we must perish,

for we are mortal men.

You, the Giver of Life, you have ordained it.

We wander here and there

in our desolate poverty.

We are mortal men.

We have seen bloodshed and pain,

where once we saw beauty and valor.

We are crushed to the ground,

we lie in ruins in Mexico and Tlatelolco,

where once we saw beauty and valor.

Have you grown weary of your servants,

are you angry with your servants,

O Giver of Life?

The Fall of Tenochtitlan/Tlatelolco

Our cries of grief rise up, and our

tears rain down - for Tlatelolco is lost.

The Aztecs are fleeing across the lake,

they are running away like women.

How can we save our homes, my people?

The Aztecs are deserting the city,

the city is in flames,

and all is darkness and destruction.

Weep my people,

Know that with these disasters

we have lost the Mexican nation.

The water has turned bitter, our food is bitter.

These are the acts of the Giver of Life.

|